The Blind People and The Elephant: Creating Cross-Disciplinary Solutions to Youth Addiction with UT Powerhouse Dr. Lori Holleran Steiker

By Kayla Reed

(Texas Overdose Naloxone Initiative (TONI) kits include: Vials/muscle syringes and/or nasal spray Naloxone, alcohol pads for sterilization, rescue breathing masks, rubber gloves, educational inserts with instructions in English and Spanish, and written materials about overdose prevention and using Naloxone).

One look into the office of Dr. Lori Holleran Steiker is enough to express the dedication she has for her life’s work in adolescent substance abuse disorders. Boxes filled with supplies for the Operation Naloxone Expansion are stacked to the ceiling, and she excitedly tears one open to show off sturdy, zippered bank bags containing life-saving Naloxone kits.

Coming to UT

Dr. Holleran Steiker first came to the University of Texas in 2000. She describes her contributions to the university as a braid of personal experience, professional insight, and innovative, applied, interdisciplinary research.

She explains that her passion for recovery began with her own family. At the age of ten she witnessed a transformation free from stigma as her mother, suffering from genetically inherited alcoholism, underwent treatment and achieved a life of sustained sobriety and recovery.

Identifying early “red flags,” during college, she embarked on her own recovery journey. Her passion to help young people with substance use disorders grew from her love of recovery and from the sadness at seeing others suffering.

After college, grad school, marriage, and a move to Phoenix, Dr. Holleran Steiker sought out opportunities where she could continue helping people with substance use disorders and their families. She struggled to find a position that valued and appropriately paid for the work of a youth addictions counselor.

“I sort of marched my way over to the Arizona State University School of Social Work with my resume. I put it down on the desk of the first person whose door said ‘Director’ and was like ‘Why doesn’t Phoenix have real positions for a person with a Masters degree and expertise with adolescents with addictions?’ The man looked at me, down at my resume, and said ‘Actually, I think I have a job for you.’”

She was offered a position setting up social services for elementary schools in Apache Junction, where a culture of drugs and alcohol were relatively pervasive. This would have been an attractive opportunity for any addictions-focused social worker, however, the position was for a doctoral student. After having her tuition waived as incentive, Dr. Holleran Steiker accepted the offer and completed her dissertation while working as a part-time clinician

An expectation of her hire at UT, the next stop in her academic career, Dr. Holleran Steiker later successfully earned a federally funded K01 Mentored Research Scientist Development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). This allowed her to continue her culturally grounded research with adolescent addicts. Among the youth she was working with when she worked in the treatment industry, about one third had a chance of recovery, one third would continually fall in and out of the system, and the rest were dying. Dr. Holleran Steiker credits these odds as one of her biggest motivators to find better and more innovative prevention and intervention solutions.

A firm believer that drug prevention programs shouldn’t be designed in “ivory towers,” Dr. Holleran Steiker used the K01 grant to fund an adaptation of evidence-based recovery curricula to specific communities such as homeless youth, incarcerated youth, and LGBTQ youth. She sought out adolescent addicts to serve as “experts” on which substances were being used, where, why, and most importantly what consequences would actually make users their age reconsider their actions. A controlled study was done with the adapted curricula by distributing original materials to some participants, the adapted versions to others, and the more successful materials for each community to a delayed control group.

When checking in with her adolescent participants (who she refers to as her “experts”) Dr. Holleran Steiker asked what it was like becoming preventionists. Many replied that, essentially, their high had be ruined. They couldn’t avoid thinking about the evidence-based materials after tailoring them to their own circumstances. Their own voices made the messages resonate.

Dr. Holleran Steiker later submitted a grant application for these dissonance-based interventions, which had been very popular in eating disorder treatment but not yet utilized in substance abuse programs. The application was scored, but not funded. After making the changes recommended by the first panel, she resubmitted. The second attempt was not scored.

As she began to evaluate the application once again, two major changes happened in Dr. Holleran Steiker’s life. First, she became the Assistant Dean of Undergraduates for the School of Social Work. Second, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

While many of her administrative responsibilities could be completed from home or with the support of assistants, Dr. Holleran Steiker’s teaching and research trajectory was put on hold for a year. Upon her return, she felt out of step with new research developments in the dynamic field of addictions. She knew she had to listen closely to what was calling her. She was advised to reach out to the gurus of her field for direction.

Recovery High Schools

This lead to Dr. Holleran Steiker reaching out to William White, who believed the best place to put her efforts were recovery school programs. With experience as faculty liaison for the UT Center for Students in Recovery (CSR) since its opening in 2004, these programs weren’t completely foreign. However, the Association of Recovery Schools (ARS) served both colleges and high schools.

Unlike alternative schools, recovery high schools serve as a place where students with serious drug or alcohol problems can relate to and support each other through continuing treatment. Research shows that 70-90% of students that have undergone traditional treatment relapse within months of returning to their original high school [1]. Many treatment centers recommend students find new friends, hobbies, and hang-out spots in recovery but fail to provide steps on how to actually integrate recovery principles into their lives for the long term.

Around the time Dr. Holleran Steiker was introduced to recovery high schools, the ARS Conference was being held in Houston at Archway Academy, the largest recovery high school in the country. The then director of the UT CSR offered her the opportunity to co-present at the event. Dr. Holleran Steiker fell in love with the youths assisting with the conference as she had never before witnessed a community of young people thriving in the way Archway students were. Their joy, love, confidence, and gratitude were palpable.

Shortly after, her interest in the potential of recovery schools drove Dr. Holleran Steiker to interview an original board member from the Archway Academy over coffee. She remembers him opening the meeting with, “The first thing you need to do to start your recovery high school in Austin is…” before being quickly cut off. Dr. Holleran Steiker explained that she wasn’t sure if she would have time for such a project, or if the need for a recovery high school was even present in Austin. The board member listened patiently, waited for her to finish speaking, and repeated, “The first thing you need to do to start your recovery high school in Austin is…” He insisted that she return to Austin and genuinely share her experience and enthusiasm with as many people as possible. If Austin was a fertile ground for a recovery high school, the need would make itself clear. He stated, “If the school is really needed, it will be as if it already existed but was invisible and you needed to slap paint on it!”

University High School, Austin’s first sober high school, was founded by Dr. Holleran Steiker in 2014. In its inaugural year, the school supported 10 students. University High School has tripled that figure this year and now boasts 15 graduates, several of which have applied to and been admitted to UT.

The success of recovery high schools is largely attributed to their ability to provide support for adolescent addicts after treatment. One form of this support comes from alternative peer groups (APGs), or physical locations students are expected to be after school hours. APGs serve as sources of entertainment, hangout spots, and study groups for students away from their original triggers. They build a community that even graduating students can remain a part of.

University High School is the first recovery high school to be formally associated with a university. It is officially a UT Charter School. It’s students receive formal mentorship from those in the recovery program at UT, which shows the youths they can pave a way to a sober future.

Dr. Holleran Steiker argues that acute care simply isn’t enough; we must treat addiction like the chronic disease that it is. Like cancer, addiction doesn’t just “go away.” Unlike cancer, there is no system in place for following up with patients after treatment for addiction. As someone in remission, Dr. Holleran Steiker reports commonly receiving calls about mammograms and other check-ups; she doesn’t receive the same support in her long-term addiction recovery.

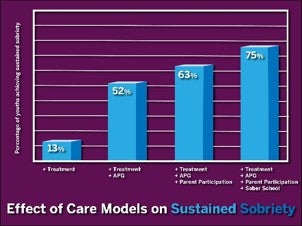

Treatment alone allows about 13% of adolescent addicts to achieve sustained sobriety. Belonging to an alternative peer group throughout or following traditional treatment raises those odds to 50%. With treatment, an APG, and parent participation, 63% sustain sobriety. With the addition of a recovery high school, 75% of youths will get well [2].

In fact, Dr. Holleran Steiker notes, some individuals who were a part of APGs in the 70s have grown up to be addiction counselors and have started their own APGs. She mentions a 60 year old friend with 45 years of recovery under her belt. This is what she says the media gets wrong, focusing on the nightmares instead of the dreams coming true.

For the recovery system being built in Austin, true interconnection will be the mark of success. Should a family in need come to any associated organization, they would be connected to all other partners that could be beneficial. For example, if a Westlake High School student approached Sage Recovery for assistance, they could be directed first to University High School. They could also be introduced to the University’s CSR members for mentorship or a softball league at Recovery ATX. Connections can even be made for those who are living with actively addicted parents and need recovery housing. There would be no wrong door. The varied missions of each branch would be united by the common mission of saving young people’s lives.

Dr. Holleran Steiker believes competition between agencies is just as big of a hurdle for recovery as the stigma surrounding addiction, a topic which she delves into in an article co-authored by CHC Director Mike Mackert [3]. Without an entire system of care and evidence that it is working, people won’t be motivated to seek out these services.

Pop-Up Institute

Holleran Steiker is one of the core members of Austin’s Recovery Oriented Community Collaborative that works together to fill in gaps and enhance addiction prevention, treatment, and recovery services in Central Texas. The professionals working with youth and emerging adults formed the Youth Recovery Network - funded by St. David’s Foundation - to strengthen the safety net for youth/families with substance use disorders. The ambitious group applied for the MacArthur 100 & Change competition, which selects teams to receive $100,000,000 of funding for a single proposal that “promises real and measurable progress in solving a critical problem of our time.” Out of what Dr. Holleran Steiker estimates as 2,000 applications, the team ended up as one of the top 200, giving new meaning to the “Top 10%.”

Though the semi-finalist title didn’t provide a grand sum of money, it did provide the motivation to bring together individuals who were “too busy” or concerned with “mission drift” when Dr. Holleran Steiker was first finding her place on the Forty Acres. To sustain this collaboration, she jumped at the chance to submit an application for a pop-up institute as a part of the new interdisciplinary initiatives of the VP for Research at UT Austin.

After securing $22,500 of funding from various relevant department heads buying in, the VP of Research Office made a matching contribution for a grand total of $45,000 for the institute. Among other efforts, the institute seeks to design comprehensive and effective services for transition-aged youths and their families, provide warm hand-offs from medical care to the community, increase dialogues between disciplines to create innovations, and create a web presence for a centralized source of recovery information.

One particularly successful portion of the pop-up institute, the Operation Naloxone Expansion, is now funded by $3,000,000 of Texas Targeted Opioid Response (TTOR) grant money. This project has provided training for all UTPD officers, mental health service providers, Resident Advisors, pharmacy students, and a significant number of social work students on the UT campus. This team is working to raise awareness about the opioid epidemic, primary prevention, and overdose prevention through trainings and Naloxone distribution.

It often seems as if different languages are spoken across fields, and Dr. Holleran Steiker argues it takes interdisciplinary efforts such as the institute to build the relationships needed to overcome this hurdle. She references a conversation between Michela (Micky) Marinelli, a neuroscience professor who does research with adolescent rats, and Julie McElrath, the Director of University High School, overheard at a luncheon for the institute’s members.

“Micky casually leaned over and said, ‘You know I found something with my rats that I’m sure has implications for your work with your students…’ Who else is having these conversations? This institute gives people the opportunity to step out of their silos and see how their work could be effectively integrated with others.”

For those struggling to step out of a particular silo, Dr. Holleran Steiker recommends starting small. Have a conversation with someone in a different department whose work is closely related to your own, and build out.

The formal pop-up institute, as funded by the VP of Research office, ends in May of 2018. A year of work will culminate at Dell Medical School with a nationally-streamed interdisciplinary Youth and Opioids Town Hall meeting followed by a day-long summit featuring experts from across the country. A candlelight vigil from Dell Medical School to the Capital honoring those who lost their battle with addiction will close the Town Hall. For more information, she encourages all to visit the Pop-Up Institute’s growing website, directory, and calendar (http://sites.utexas.edu/youthsubstancemisuse/)

The Future of Youth Substance Abuse Prevention

Dr. Holleran Steiker highlights the similarity between complex issues like adolescent addiction and the metaphor of the blind people and an elephant.

When issues are examined from a bio-psycho-social-spiritual, or holistic, perspective they can be understood more completely than if only through the lens of a particular field. Her determination to spread this approach doesn’t end in the research community, rather she sees that it is carried over into classrooms.

As of this past September, Dr. Holleran Steiker is now Director of Instruction, Engagement, and Wellness at the UT School of Undergraduate Studies (UGS). She leads enhancements to UGS Signature Courses to encourage holistic perspectives across subject matter. Instead of traditional lectures, Dr. Holleran Steiker’s students meet local experts, visit six different labs across campus to experience the work of addictions researchers, and experience panels of students from University High School and other recovery settings. The students all engage in an applied project related to her various projects and they become a part of the solution.

Dr. Holleran Steiker’s new position and leadership of the Pop-Up Institute reflect years of personal and professional dedication. Her work has impacted families across the state and fostered the community of interdisciplinary research developing on campus. She sees herself first as a connector, committed to bringing together different disciplines under the goal of addressing this very pressing public health issue. When it comes to recovery, Dr. Holleran Steiker believes there is always more that can be done and we will always do more together.

[1]Finch AJ, Moberg DP, Krupp AL (2014) “Continuing care in high schools: A descriptive study of recovery high school programs.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse 23: 116-129.

[2]Rochat R, Rossiter A, Nunley E, Bahavar S, Ferraro K, et al. (unpublished manuscript/PPT). APGs: Are they effective?

[3]Michael Mackert, Amanda Mabry, Katharine Hubbard, Ivana Grahovac & Lori Holleran Steiker(2014) Perceptions of Substance Abuse on College Campuses: Proximity to the Problem, Stigma, and Health Promotion, Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 14:3, 273-285, DOI: 10.1080/1533256X.2014.936247